Getting Started in Stereo Photography

by

Steve Kiesling, Detroit Stereographic Society

The

best cue to the apparent depth of any scene comes as a result of our

"binocular vision" - the ability to instantly process the two

different views our eyes see and fuse them together into a single

"solid" image with height, width, and depth. This effect is

especially noticeable up to about 100' or so, gradually decreasing in

intensity with distance.

The

principle behind stereo or "3-D" photography is simply to simulate

our normal binocular vision, using two images which correspond to what each

eye would normally see. This

typically involves the use of a "stereo" camera, having two

identical lenses separated by a distance approximately equal to the distance

between your eyes. Two regular

single-lens cameras mounted side-by-side can also be used, by simply

activating both shutters at the same time.

And for stationary subjects, one

single-lens camera can be used, moved appropriately side-to-side to obtain the

two images. Whatever the method,

the resulting right and left pictures, when viewed so that each eye sees only

its particular image, seem to fuse into one view having all the depth of the

original scene. This technique is

unsurpassed for creating images with maximum realism and impact.

Stereo

images have been around for over 150 years.

The most popular commercially produced formats have been the stereoview

cards, lenticular prints, 3-D movies, and the View-Master reels.

In addition, amateur stereographers have made millions of their own 3-D

images, especially since the introduction of the Stereo Realist system in

1947.

The

good news is that all these formats (and more) are still available to

stereographers today, and thousands of people around the country and the world

are actively engaged in producing

Because

stereo images can be made in so many formats, one of the first steps in taking

stereo pictures is deciding what you want the finished product to be.

For our purposes here, we will concentrate only on "still

image" formats and equipment, leaving other formats such as film, video,

computer-generated 3-D and holography for another time.

Stereo Print Systems

In

the print format, the most common

type traditionally has been stereoview cards, which have separate left and

right images mounted side-by-side. These

are typically viewed through a stereoscope, which has two lenses in a small

covered housing, and a wire frame on a wooden bar in front of the lenses to

hold the card. Focusing is

accomplished by sliding the card frame towards (or away from) the viewing

lenses. The most common size for stereoviews is 3-1/2" by

7"; however, both larger and

smaller cards have been produced. Commercially

produced mounting cards are available, and some view makers produce their own

custom-made cards as well. Images

for these cards can usually be made using any type of camera; however, the old

“Sputnik” and the new “3D World” medium-format stereo cameras are

particularly well-suited for making stereoviews, due to their use of 120 roll

film which produces large 2-1/4" negatives.

Stereoviews have become a popular stereo format now that computer-based

imaging has made it easy to do.

View-Magic Print Viewing System

Another

way to view stereo print pairs is with a device called the

"View-Magic" print viewer. This

inexpensive viewer uses four mirrors to allow viewing of stereo print pairs

mounted vertically, one above the other, instead of side-by-side.

The advantage of this system is that stereo prints of nearly any width

(including panoramic prints) can be very easily viewed in 3-D.

Though the View-Magic viewers are no longer in production, similar

viewers are available.

Lenticular

Stereo Prints

A

different stereo print format which has long been popular is the

"lenticular" 3-D image. These

pictures use a special printing process where extremely thin slices of the

images are aligned vertically behind a clear, finely-ridged lenticular

material. This material acts as a

lens to direct the slices of the right and left images to the appropriate eye.

A special 3- or 4-lens camera (such as the Nimslo, Nishika, ImageTech

3-D Wizard, 3-D Magic, and others) is usually required to produce the original

images, and the film must be sent to special labs for processing.

The advantage of this format is that it allows you to easily view these

images without special glasses or viewers.

Argus

Print Viewing System

For

simplicity and convenience, this system is hard to beat.

The Argus stereo camera (also found under the “Loreo” and

Discovery” labels) uses a special mirror arrangement inside the camera and

an angled film path to take 3-D pictures that require no special processing or

mounting. Just load in a roll of

400 ASA film, decide whether you want to use the built-in flash, and shoot

away. There are no settings to

adjust, and any subject from 2-1/2' to infinity will be in focus.

Because the images are compatible with standard print processing

equipment, prints can be quickly and inexpensively made, and immediately

viewed with the included viewer. For

many people, this is an ideal way to begin making their own 3-D prints.

Stereo Slide Systems

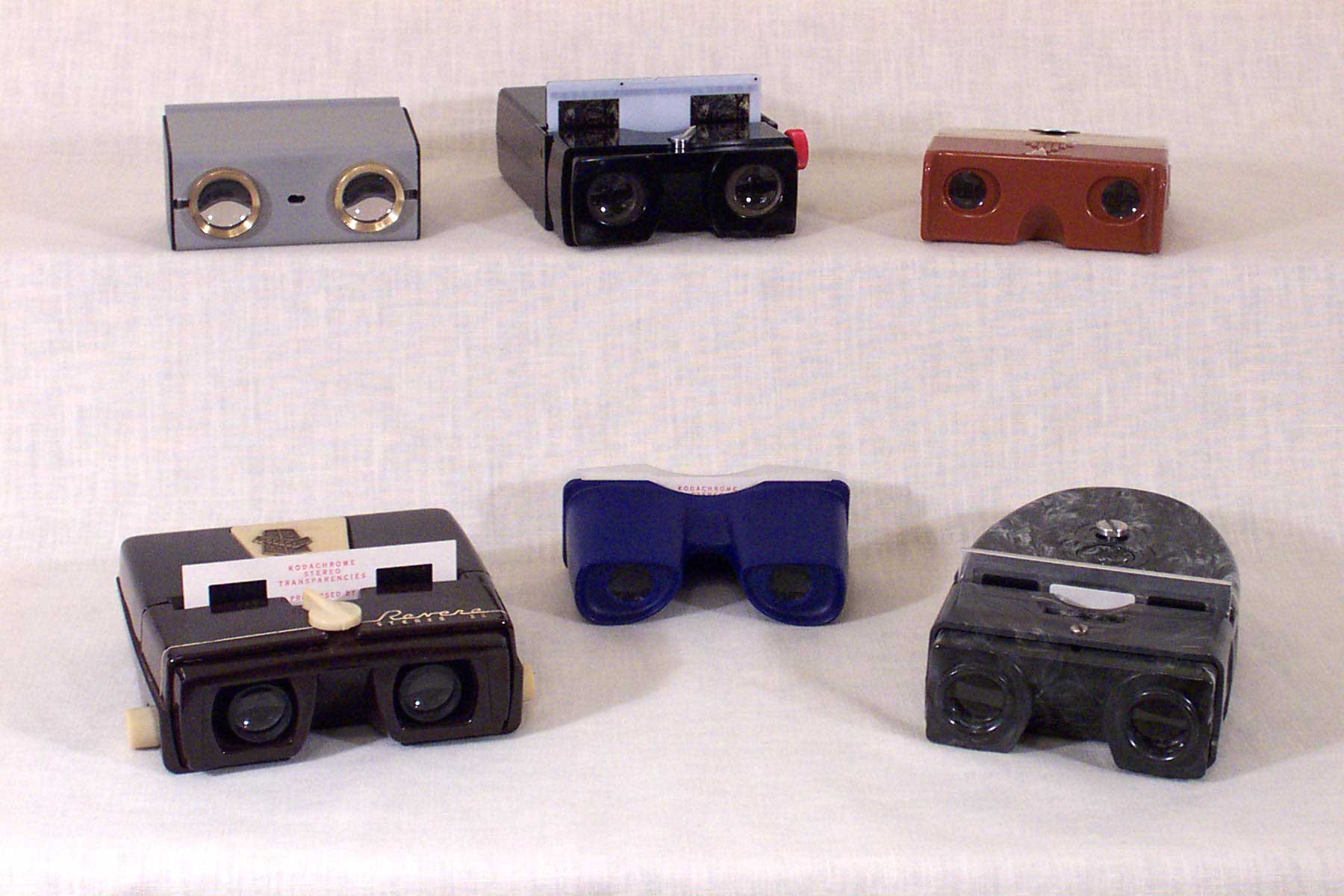

The vast majority of stereo photography since 1947 has been done in the Stereo Realist format, or a modified version of this format. This system uses standard 35mm transparency film in dual-lens cameras, and takes left and right images that are nearly square in shape. These images are then mounted in a 1-5/8" by 4" mount for viewing or projection. Over a quarter-million of these cameras were manufactured in the 50's and 60's, and many of them are still in use today. The most commonly available models are the Stereo Realist, the Kodak Stereo, the Revere 33 Stereo, and the TDC Stereo, though dozens of other cameras of this type can be found as well.

Standard

"Realist" pictures are about 5 "sprockets" wide (compared

to the standard 8-sprocket image taken by most modern cameras), and most

stereo mounting, viewing, and projection equipment has been designed for

images of this size. A few stereo

cameras have been made which produce wider (7-sprocket) images, and superb

stereo pictures can also be made using regular single-lens cameras either

alone (for stationary subjects) or "twinned".

Once

your slides have been mounted, you have the option of viewing them either in a

hand-held viewer or on a silver screen, using a stereo projector.

There are many stereo hand viewers available, ranging in price from a

few dollars to well over $100. Most

have adjustable focusing and a built-in light source;

some also have glass lenses and have an interocular (eye spacing)

adjustment. The Realist ST-61

"red button" viewer is the most popular, but there are dozens of

different models available.

There

also are many stereo projectors to choose from, most of them costing from $200

to $450.

The

most common models are the TDC 116, the TDC 716, and the Compco Triad.

Some newer projectors are also available, but at much higher prices.

A pair of Kodak Ektagraphic III projectors can also be used for slides

in standard 2” x 2” mounts, needing only the addition of polarizers in the

light path. With any of these

projectors you must use a silver screen

(not white), and special polarized glasses.

View-Master

System

Known

around the world for the millions of commercially-produced reels, the

View-Master system is also a format for the amateur stereographer, though it

is not as popular as the other systems already mentioned.

Two cameras in particular - the View-Master Personal and the

View-Master Mark II - were manufactured for the purpose of making your own

personal reels. Both cameras use

standard 35mm film. Blank reels

and insertion tools are available (though not always easy to find), but a

special film punch is required which is fairly expensive (currently around

$300). If you do not take enough

pictures to justify the purchase of a punch, one alternative is to send your

film to a mounting service and have this done for you.

View-Master reels can be used in any of the View-Master viewers, or

projected using the View-Master Stereomatic 500 projector.

Again, a silver screen and polarized glasses are required when

projecting these reels in stereo.

Taking Stereo Pictures

As

you begin taking stereo pictures, you will find there are some differences in

the way you approach stereography compared to regular planar photography.

For example, you will want to compose your pictures to take advantage

of the depth you are now able to show. One

rule of thumb is that a good stereo image will contain at least three planes

of depth; fore-ground, middle-ground, and back-ground (the more planes, the

better). For best results, keep the range of depth in your scene approximately

within the range of depth available for a lens aperture of

f 8, even though you may be actually using a different aperture size.

Another

difference is in the way you adjust your focus, aperture, and shutter speed

settings. In stereo photography

you will usually want to obtain the maximum depth-of-field possible, since

pictures that are sharp from front to back help to maintain the realism of the

scene. As a result, your lens

openings (f-stop settings) will tend

to be higher (f 5.6 to f 11), and your shutter speeds a little lower (1/100 sec. or so);

the exact settings depending of course on the amount of light available

and the sensitivity of the film you use.

It is usually best to select films with a minimum of "grain"

to help reinforce the realism of the picture.

This

larger depth-of-field makes the exact setting less critical;

however, it is a good idea to take advantage of the "hyperfocal"

markings on the camera to obtain the maximum sharpness over the widest

possible range. These markings

are typically on the side of the lens or on the focusing dial, and show the

range of distances which will be in focus for a particular focus setting at

different

f-stops.

For example, if you set your focus at the hyperfocal distance of 20' at

an aperture of f 8, everything between 10' and infinity will be in focus.

If the most distant part of your image is only 20' away - say, for an

indoor picture - setting the focus at 10' (again at f

8) will give you a sharp image from 6'8" out to 20'.

These distances can also be obtained from depth-of-field or hyperfocal

tables. Using this information

can help you to maximize the sharpness and realism of your 3-D pictures.

Tips for using Stereo

Cameras for 3-D

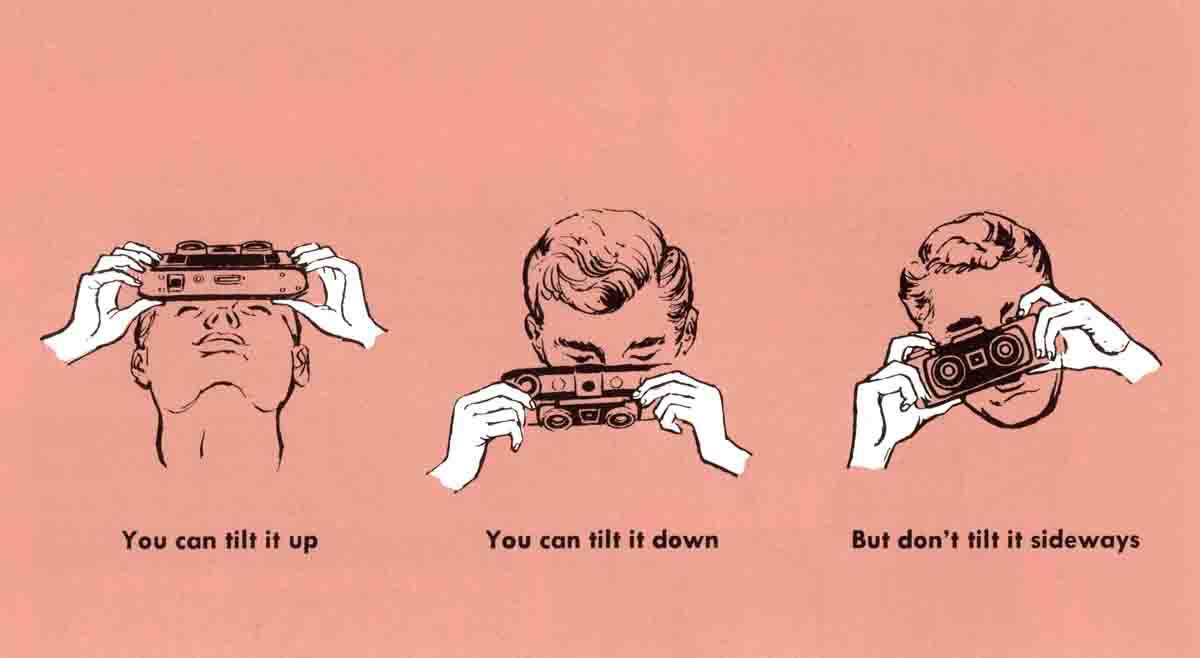

When

you are using a stereo camera, it is important to keep the camera level from

side to side (it’s okay to aim it either up or down).

Some cameras have a built-in bubble level to help with this.

Your

nearest subject should generally be no closer than about 7', especially if your

image will extend out to infinity. If

you want an object to appear to come "into the audience", it should be

closer than 7'; however, you should

compose your picture so this object doesn't "touch" the edges of the

frame within about 10' from the camera. If

the most distant part of your scene is 20' or less (as with an indoor picture),

the nearest subject can be as close as 4" away.

Some

stereo cameras will exhibit "vignetting" or darkening of the image

corners with apertures of

Using

a light meter is also a good idea for getting the best exposures, particularly

when using slide film. Most of

these cameras have no built-in metering capability.

Most

stereo cameras have some type of internal marking system to help identify the

left and right images, called "witness marks".

A good way to do this, however, is simply to check the frame numbers on

the edge of the film - the right image will almost always have the lower

number.

Tips for using

Single-Lens Cameras for 3-D

If

you use one or more single-lens cameras for stereo, you'll have a lot

of flexibility with respect to lens focal lengths and "interocular"

distances between the two images. In

many cases an SLR camera is preferred for stereo pictures of very close and very

distant subjects. Several

"slide-bars" and adjustable platforms are available for taking

pictures with base distances different than that of a standard stereo camera. Take extra care to keep the heights of the left and right

images in their mount exactly the

same, and make sure there is no "twist" in either picture (this

applies to "twinned" camera setups as well).

And be sure the only thing that moves during the time between taking the

left and right images is your camera! This

includes cars, water, flags, passing airplanes, etc. - any object that appears

in the image area. If you use a

flash, it must also remain stationary and be separated from the camera.

Summary

Stereo

photography is a fascinating and powerful visual medium.

It is simple enough that anyone with any

camera can get started in it, and sophisticated enough that you can spend a

lifetime exploring it's intricacies. It

is very rewarding on its own; and

for those who enjoy the challenge of competition, there are many opportunities

available for you to test your skills.

There

are many good sources of additional information on stereo photography.

Organizations such as the National Stereoscopic Association, the

International Stereoscopic Union, and the Photographic Society of America all

have a lot to offer anyone interested in stereo photography.

If

you have internet access, I encourage you to log onto the web site www.stereoscopy.com

and explore the many 3-D related links listed there.

The

Detroit Stereographic Society meetings are a great place to see and learn about

stereo, and you’ll want to visit their web site, www.Detroit3D.org,

too.

I

hope this information will help encourage you to try your hand at stereo

photography.

If

there is anything I can do, please send an e-mail message to me at Steve.Kiesling@att.net,

or give me a call at (734) 595-0245, and let me know how I can help.

This page was last updated on 03/08/2008.

Copyright © 2001-2008 Detroit Stereographic Society. All

rights reserved.